Who is better at penalties? Men or Women?

Comparing the penalty-taking abilities of men and women.

Analysing Men’s and Women’s Football Penalties

1. Introduction

I recently came across a dataset that had historic penalty performance for a variety of football matches over the past twenty-or-so years. The data has in it both men’s and women’s performances so I thought it might be interesting to compare and contrast the performance of each, particularly given the increase in popularity of women’s of the last few years. The code for this analysis can be found on my Github:

It was found that the success rate of women’s performance varied quite strongly over time, while the men’s performance was relatively consistent in comparison. This led to a few further insights:

- Prior to 2018, the women’s conversion rate can be up to twenty percentage points higher than the men’s conversion rate.

- After 2018, the women’s conversion rate drops to nearer to the male conversion rate.

- These differences are statistically significant.

2. Analysis

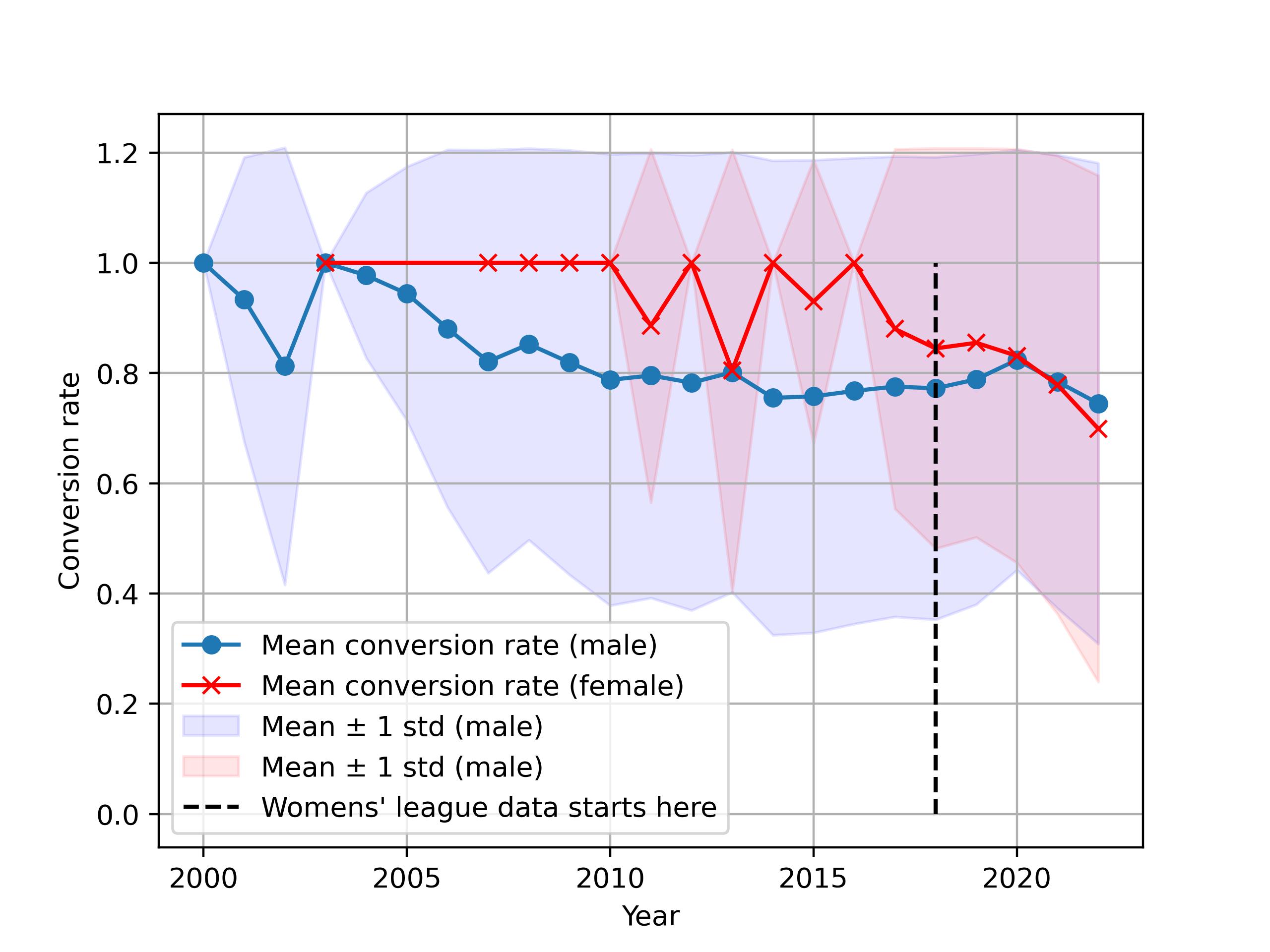

The first step of the analysis was to evaluate the mean conversion rate for each gender over every year in the dataset as shown below.

| year | mean_male | num_penalties_male | scored_male | mean_female | num_penalties_female | scored_female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 1.000000 | 73 | 73 | 1.000000 | 8 | 8 |

| 2007 | 0.820896 | 536 | 440 | 1.000000 | 7 | 7 |

| 2008 | 0.852273 | 528 | 450 | 1.000000 | 7 | 7 |

| 2009 | 0.819113 | 586 | 480 | 1.000000 | 12 | 12 |

| 2010 | 0.787572 | 692 | 545 | 1.000000 | 18 | 18 |

| 2011 | 0.795518 | 714 | 568 | 0.885714 | 70 | 62 |

| 2012 | 0.782421 | 694 | 543 | 1.000000 | 40 | 40 |

| 2013 | 0.801460 | 685 | 549 | 0.804348 | 46 | 37 |

| 2014 | 0.754941 | 759 | 573 | 1.000000 | 19 | 19 |

| 2015 | 0.757616 | 755 | 572 | 0.929577 | 71 | 66 |

| 2016 | 0.767492 | 929 | 713 | 1.000000 | 51 | 51 |

| 2017 | 0.775408 | 797 | 618 | 0.880000 | 125 | 110 |

| 2018 | 0.772242 | 843 | 651 | 0.844660 | 206 | 174 |

| 2019 | 0.788560 | 979 | 772 | 0.854839 | 310 | 265 |

| 2020 | 0.823759 | 1027 | 846 | 0.831169 | 231 | 192 |

| 2021 | 0.784272 | 941 | 738 | 0.778443 | 334 | 260 |

| 2022 | 0.744845 | 776 | 578 | 0.699029 | 309 | 216 |

Plotting these results (including standard deviations, which are omitted from the table) we see that there is some interesting behaviour. The simplest to see is that after about $2005$ the male conversion rate settles around $80\%$. Looking at the number of penalties, we can be reasonably confident in this figure as only year $2003$ has a small number of penalties; the remaining years have in excess of $500$ penalties taken by men for that year. On the other hand, the women’s figure is initially very noisy which is likely a consequence of having relatively few penalties included in the data. Only at year $2017$ are more than $100$ penalties included. One feature of this data that is important is that in $2018$, women’s league data is included, but it already appears that the general trend of conversion rate approaches that of men’s when enough penalties are included; adding the league data seems to strengthen this trend.

2.1 Results 1 and 2

This plot shows that after about $2007$, the male conversion rate is stable, meanwhile the female rate is noisy. The two rates are similar after $2018$, indicating a slight change in behaviour. The change in rate for females looks to appear at abour $2016$, however, the scale of data is still smaller in $2016-2017$ compared to $2018$ onwards so we use this as the point of demarcation, especially since this is when the women’s league data is included.

Prior to $2018$ the women have much less consistent standard deviations which could be due to the relative scarcity of data compared to the male dataset (sometimes the there are more than $10\times$ more male penalties than female penalties in a year). Once the number of penalties recorded is on the same scale, the deviations look similar.

In summary, there is a shift in performance before $2018$ and after $2018$ for women.

Male performance is roughly similar throughout. In the time period up to $2018$ womens’ conversion rate noisily moves between $0.8$ and $1.0$ which is about $20$ percentage points higher than the typical male conversion rate.

This large difference does suggest that behaviour is different between male and female takers prior to $2018$.

Result 3

We employ hypothesis testing to more emphatically answer is there a difference in penalty conversion rates between men and women? The attributes we test for independence are gender and conversion_rate in the original data. If conversion_rate is statistically independent of gender, then we would expect that the conversion rates should be similar, irrespective of the whether gender == male or gender == female.

Test details

- We use the chi-squared test for independence which is valid since we have categorical input variables, all observations are assumed to be independent, the sample size is large (in this context large means greater than $\approx 5$ as otherwise we would use a different test) as in total it is on the order of thousands of observations.

- We test the null hypothesis that there is no statistical difference in penalty conversion rates between men and women.

- Roughly speaking, this test evaluates the difference between an observed count $O$ and and expected count $E$ under the null hypothesis and evaluates $\sum_{i,j}(O_{ij}-E_{ij})^2/E_{ij}$.

These values are summed over all cells in the $2 \times 2$ possible output space $(i,j) \in \{\text{Gender} \times \text{Scored}\}$. If this sum is large, then the observed values are far from what is a likely observation under the null hypothesis so we reject the null hypothesis as it yields an unlikely result. - The degrees of freedom (dof) for the test is $(nrows - 1)(ncols-1) = (2-1)(2-1) = 1$.

Test Results

- For the full time period, the chi-squared test statistic is $9.745$ which has a $p$-value of $0.0018$.

We can reject the null hypothesis at the $\alpha = 5\%$ level as $\alpha$ is larger than $p$. This is often a sufficiently fine level to reject the null hypothesis. So there is a statistically significant difference in conversion rate between men and women. - Pre-2018 Analysis: Chi-squared value is approximately 40.124 with a p-value of about $2.38e-10$, indicating a very strong statistically significant difference in penalty conversion rates between men and women before 2018.

- 2018 Onwards Analysis: Chi-squared value is approximately 0.741 with a p-value of $0.389$. This suggests that there is no statistically significant difference in penalty conversion rates between men and women from 2018 onwards.

In conclusion, although it may have historically seemed that women had a better conversion rate, more recent evidence is not strong enough to maintain this position.